Influenza A(H3N2) subclade K: when “seasonal” stops being predictable

Influenza is often treated as a seasonal inconvenience but still predictable, manageable, and largely known. Subclade K of influenza A(H3N2) is a reminder that seasonal does not mean stable, it means that we should be prepared every season (Chen, 2026). This virus is not unprecedented, but it exposes a recurring vulnerability; our vaccine and preparedness systems move on fixed timelines, while influenza evolves on its own schedule.

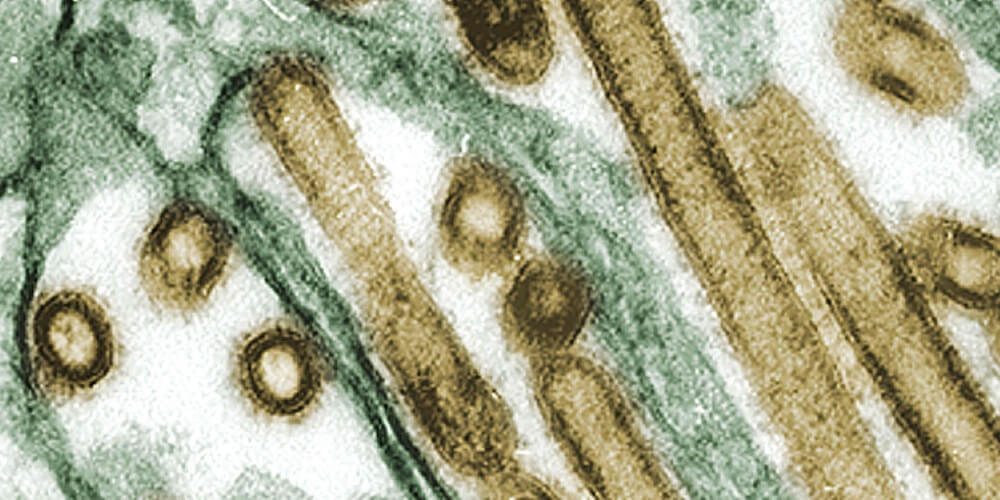

Subclade K (often labeled J.2.4.1 in current phylogenetic systems) is a recently expanded A(H3N2) lineage . It rose quickly from low-level detection to wide geographic spread after August 2025 (Hadfield et al., 2018). On its own, the emergence of a new H3N2 subclade is not shocking, but a normal consequence of antigenic drift.

The issue is that current influenza vaccine production is long and cumbersome (Krammer et al., 2018) and strains to be included in seasonal vaccines must be selected at least six months in advance to allow for sufficient production, distribution, and rollout. Indeed, K was first identified after the vaccine strain selection decision point (spring 2025 for the western hemisphere 2025–2026 formulation). The CDC notes these viruses are antigenically drifted compared with the A(H3N2) vaccine component, meaning we should expect reduced protection against infection and mild disease, especially in groups whose immune histories already struggle with H3N2 drift.

Vaccine mismatch is not a new thing (Krammer et al., 2018). It is commonly the case that the strains included in the vaccine are not the circulating strains when the season arrives (Chambers et al., 2015). Furthermore, the whole vaccine production process may introduce egg-specific adaptations that reduce vaccine effectiveness (Jung et al., 2021; Zost et al., 2017). Indeed, a similar mismatch for the H3N2 component happened in the 2014-2015 season (Chambers et al., 2015).

With the emergence of subclade K, multiple regions saw earlier-than-usual increases, and K detections expanded across many countries. WHO describes a “recent and rapid rise” and notes that K has been detected in dozens of countries within months. One issue is that healthcare disruption is driven by volume, timing, and concurrency of cases. H3N2-predominant seasons have a well-known tendency to hit older adults hard (Langer et al., 2023), and outbreaks in care settings can amplify impact rapidly. Sensationalising headlines, highlighting “superflu” also contribute to vaccine hesitancy and diminished uptake (i.e. “why should I bother?”) further compounding the problem. Indeed, “reduced” does not mean zero and despite the mismatch, early ECDC data suggests vaccines still provided meaningful protection against medically attended A(H3N2) in primary care (reported range ~52–57%). WHO similarly points out that, despite antigenic differences, early data indicated protection against hospitalisation remained in expected ranges (roughly higher in children than adults).

So what should the strategy be?

Clearly this question can be answered at several levels.

-

Immediately, the key is not to oversell vaccines as infection prevention, but rather as severity prevention. At the same time, aggressive vaccination campaigns are needed to increase the uptake in the at-risk populations, including the elderly. Uptake remains below the 75% target in most EU countries. This includes Sweden, where coverage in over 65 year-olds has recently been below 70%.

-

Clinical pathways must be optimised to reduce avoidable severe disease. Rapid testing and early antiviral treatment for vulnerable patients, particularly in primary care and long-term care, are practical measures that can reduce hospital burden during high-incidence periods.

-

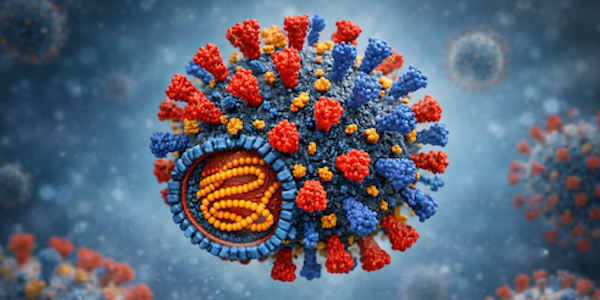

Finally, we need to modernise the vaccine pipeline. The current approach relies on prediction and long lead times (Krammer et al., 2018). New modalities and strategies that can shorten update cycles or broaden protection across multiple strains, and ideally across multiple seasons, are urgently needed (Taaffe et al., 2024). Progress toward broadly protective or “universal” influenza vaccines has been scientifically encouraging (Arevalo et al., 2022; Bliss et al., 2024; Guthmiller et al., 2025) but operationally difficult, and the commercial landscape remains volatile, with many new vaccines showing non-superiority to current approaches. That is why public investment and diversified development pathways matter. Better seasonal vaccines and faster pivots would also strengthen readiness for pandemic influenza.

The bottom line is that subclade K is not special, but it is what we should expect when a rapidly drifting virus meets a slow update cycle. The best response is to continue pushing visibility, surveillance, and readiness. We should work to ensure higher uptake in high-risk groups, faster detection and reporting, and sustained investment in next-generation influenza vaccines.